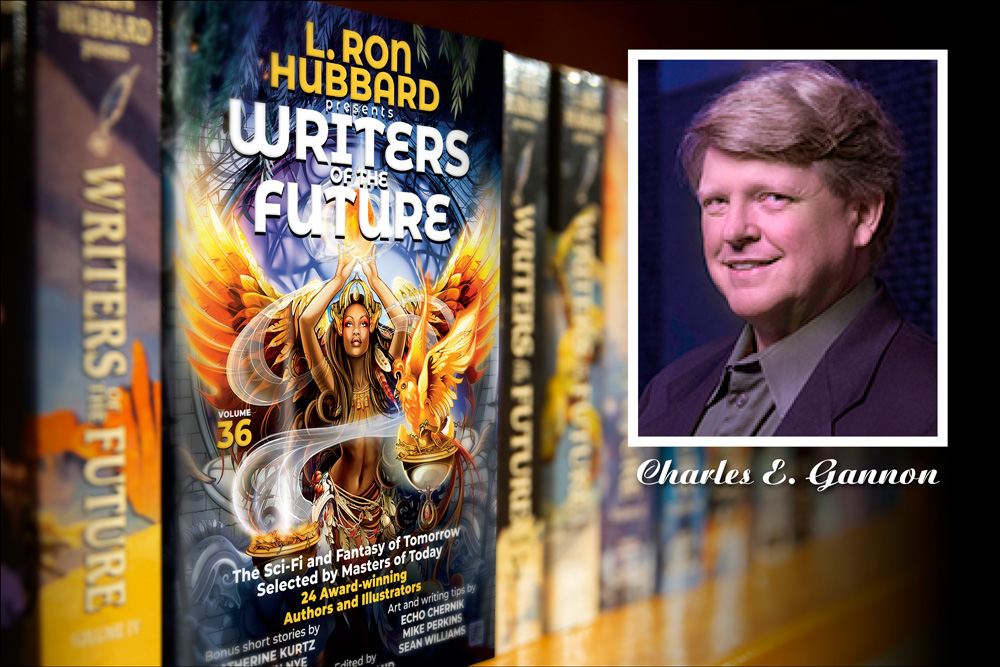

Writers of the Future Volume 36: A Review

It has been my observation—perhaps optimistic, perhaps over-kind, or perhaps just flat-out deluded—that most anthologies and collections of fiction display a species of convergent evolution. Having edited several, I have become aware of what I can only call an impulse towards collective coherence as the project takes shape. This is not the same as setting a “theme”; that is a very specific kind of commonality which, for various reasons, usually only works well if it is established at the outset. What I am referring to is more on the level of a “vibe” or unconscious motif—words that shall (not surprisingly, perhaps) recur throughout this review.

So I was not surprised (but still, very gratified) to find that the thirty-sixth volume of L. Ron Hubbard’s Writers of the Future anthology does indeed have a definite vibe and returns to a dominant motif that is every bit as much about mood as it is method or style. And happily, there are just enough stories that partially or wholly part company from that pattern to provide a contrast that refreshes the literary palate and so readies it for the next serving of the featured fare.

L. Ron Hubbard Presents Writers of the Future Volume 36 is richly populated by stories that recall (albeit in a radically different sense and context) Churchill’s quote about “a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.” So many of them, particularly in the first half of the collection, have a distinctly Gothic feel, even when the setting in no way resembles what we associate with that term. In the majority of them, the world is our own, but with a twist or a change. That difference may be overt, but just as often, it runs alongside or within our reality like the invisible thread of a secret history woven into the one we know.

L. Ron Hubbard Presents Writers of the Future Volume 36 is richly populated by stories that recall (albeit in a radically different sense and context) Churchill’s quote about “a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.” So many of them, particularly in the first half of the collection, have a distinctly Gothic feel, even when the setting in no way resembles what we associate with that term. In the majority of them, the world is our own, but with a twist or a change. That difference may be overt, but just as often, it runs alongside or within our reality like the invisible thread of a secret history woven into the one we know.

However, before entering that compelling weave of narratives, it is perhaps best to attend to the other components of the collection. Too often, they are left for last and thus may be misconstrued as comprising an afterthought, either in the opinion of the judges or this reviewer.

Illustrators of the Future

For those who are unaware, the annual Writers of the Future Contest has a twin: the Illustrators of the Future Contest. Each of the winners produces a graphic for each of the stories in the collection. It is always challenging to discuss (let alone review) art without an example to share, but this much can certainly be asserted: these illustrations are not merely “accompaniments.” Rather, they are all striking accomplishments that are uniformly noteworthy in execution, but utterly unique in style. Invariably, each offered a visualization of its matched tale that was completely different from my own, which I intend as the highest possible compliment. Why would I want to see an image that is already in my mind’s eye? Happily, the artists all chose perspectives that are fresh, challenging, and extremely diverse in style.

Essays and Perspectives

Another feature of this collection is a fine and fitting group of essays in which various luminaries of the field (both writers and artists) offer perspectives (and in most cases, sage advice) on how to approach and manage a career in science fiction and fantasy.

On the surface, the concerns raised in these articles may all appear to be disparate. L. Ron Hubbard’s oft-cited “Steps In the Right Direction” offers a recommendation that is a close cousin to one of John Steinbeck’s: that an author should groom work habits that enable and encourage the free flow of ideas and words. In this, Hubbard offers an insight into his own craft and method: to trust to instinct, even one’s moment-to-moment narrative intuition, and not tax it with in-process revision and rewriting. To summarize in a single waggish phrase, his advice to writers is: always go with the mojo.

Sean Williams’ breezy and highly practical “Making Collaboration Work for You or Co-writing with Larry and Sean” charts a very different discursive course, inviting readers to consider a list of key considerations before a writer (new or established) becomes involved in collaborative work. Speaking as someone who has a good deal of personal experience with cooperative authorship, this excellent list is so chock-full of pertinent points and tips that there is no way to really synopsize them: they all warrant close and attentive reading. However, if I feel Sean offers up one particularly crucial takeaway: make sure you want to work in collaboration with someone else. No matter how alluring certain professional and financial features of such a project may be, if you don’t truly want to do it, you will probably not do your best work and so undermine whatever you hoped to gain through the collaboration.

The final advice-focused essay comes from Mike Perkins, appropriately titled “Breaking In.” However, it contains insights that if not news to a more established professional, are very useful reminders. Perkins’ two takeaways may sound almost contradictory: love what you do, and learn to say no. However, he makes a compelling case that, in fact, being able to do the latter may be crucial to preserving the former. Specifically, he points out that when an artist becomes so overloaded by projects that what she/he used to love begins to feel like a burden, she/he has arrived at a critical professional juncture: the point where an artist has to learn to say “no.” He is refreshingly realistic about acknowledging the starving artist/writer complex: that we live on the contracts we can secure, and that therefore, live with the perpetual anticipation of the wolf at our door … even when it might no longer be there.

I remarked at the outset that the professional essays might all sound very different in content and tone … and that yet, there is a common thread. And I would say it can be encapsulated in this familiar (but reworked) axiom: “Creative, know thyself.” Or that, at the very least, we should strive to do so as well as we may, at any given point of the lifelong endeavor we sometimes demote to the quotidian term “career.” These experts and old-hands overlap along this key axis of their advice: to always keep a close measure of one’s own skills, challenges, capacities, and limits, and a grounded ability to distinguish between what next explorations are likely to be productive versus those which may sound appealing but prove to be tar pits of despair and regret.

The Collection

I shall consider the core of the collection—the stories themselves—in the order of their presentation, mostly because their sequence is clearly purposive. Specifically, part of each tale’s impact is rooted in its interesting (and often surprising) juxtaposition with the next. Indeed, the (less prevalent) stories that are built up from comparatively straight-forward scenarios and subject matter ultimately serve as anchors for those that have a more hyperbolic relationship to our world. This applies not only to the contest winners but also to the resident masters whose works, like the others, show a similar variation, ranging across the spectrum from conventional to anything but.

Leading off the collection, C. Winspear’s “The Trade” calls to mind the old adage, “Be careful what you wish for. You just might get it.” That warning gets a fresh take in this cautionary tale where humanity and Earthly life is already at critical risk when an alien representative comes bearing solutions. But which risk is ultimately greater: the dire endgame portended by our planet’s intrinsic troubles or the unknown consequences of agreeing to a deal that just might be too good to be true?

“Foundations,” by Michael Gardner, brings to mind yet another old saying: “Home is where the heart is.” But what if that were literally true, and what if it’s scope extended well beyond one’s heart? Fantasy courts allegory in this Gothic-toned tale that occasionally channels echoes of Radcliffe, Hawthorne, and Poe while laying the dramatic cornerstones of its own very distinctive exploration of the significance of what we mean by the concepts of “family roots” and “inheritance.”

Andy Dibble’s “A Word that Means Everything,” presents a first contact scenario in which genius Cartesian-nihilist xeno-octopi meet with an embassy of internally disputatious theologian/linguists from Earth. In the course of the characters’ deep dives into the benthic unknowns of ontology and cosmology, it explores how true alienness is not found in physical form, but perceptual and intellective substance. The scenario’s vibe and contents are all its own, yet there are vibes that echo the numinous wonderings and narrative impulses of James Blish.

In “Borrowed Glory,” L. Ron Hubbard spins out a secret history tale of his own. In keeping with the Gothic manner but without its full measure of darkness, he proposes a scenario which leaves us to ponder this: if Dorian Grey hadn’t been such a vain, selfish, and misanthropic monster—if instead, he had simply been an Everyman/Everywoman hungering for experiences that they had missed—how would we react to that character? And would we ourselves behave any differently than the protagonist?

“Catching My Death” by J. L. George is another tale featuring elements of the Gothic, here offset with faint hints of the macabre and furnished with a title which (like several others in this collection) repurposes a euphemistic idiom to articulate both the narrative’s literal conceit and the focus of its unfolding scenario. In this case, it is a world in which one’s “death” is an entity that each person is expected to find and capture, rather than avoid. The social—and psychological—impact this requirement has upon the protagonist and the altered mindscape of this world’s otherwise recognizable environment are rich with allegory and ominous invention.

F. J. Bergmann’s sly and yet familiar, “A Prize In Every Box,” recalls the devices and structures of the very best (and most provocative) of the Golden Era masters but with freshly reimagined sensibilities and no shortage of sideways grins at the timeless rituals of quotidian existence. All of that is centered around an enigmatic box that makes impossibilities not only possible but real—and either lethal or life-giving, depending upon who wields it, when, and for what purpose.

In “Yellow and Pink,” Leah Ning forges another link in this collection’s chain of Modern Gothic ruminations. This one may combine (hold on now…) vibes reminiscent of both Groundhog Day and Edge of Tomorrow but rises far above them in positing the question of how far we will go to save another if we have endless opportunities to do so? And, more ominously, how we might come to confuse that with saving ourselves.

In “The Phoenix’s Peace,” Jody Lynn Nye brings a whole world into being … on what is the narrative equivalent of the back of a matchbook. Using authorial strokes as elegant and economic as those of a Japanese master’s inkbrush rendering an impressionistic image of a horse in motion, her story conveys more action—both external and internal—than it would seem mere words could impart. And despite the constraints of the length, it is also brim-full with Jody’s trademark grace notes of wit and wry social observation.

“Educational Tapes” breaks with the mood of the collection in a manner I can only call arresting in its terrifying eloquence. Author Katie Livingston evokes echoes of the more plausible dystopian threads in our cultural consciousness, orbiting the same center of gravity as Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, Zemiatin’s We, and Lucas’ THX-1138. However, its structural and aesthetic ambitions set it apart from any peers. It is an epistolary tale told by an unnamed narrator and unfolds along so ragged an edge that each seems to teeter on the edge of suborning and subverting itself, and each other. Which, it is tempting to speculate, is not only one of the story’s objectives, but is a seed of cautionary insight regarding what could germinate in our own world.

“Trading Ghosts,” by David A. Elsensohn, is yet another story with a title at once thematically tantalizing and yet utterly literal. This time, Modern Gothic takes a turn down a dark noir alley in a science fictional universe of broken dreams and uncertain outcomes. The setting is wonderfully consistent and yet wonderfully unwilling to lay itself out in toto. It’s a place where an angel that wants to die, but can’t—and a human that wants to live, but is no longer fully aware of what is keeping him dead, both inside and out. And when you get to the strange answer that lies at the final conjunction of their respective dramatic trajectories, you’ll appreciate the title all the more.

“Stolen Sky” by Storm Humbert is a science fiction story built along the lines of underlying elegy and the tragedy of how even well-intentioned cultural contact can have (un?)intentional consequences. We see a human-dominated universe through the eyes of a likable and relatable non-human whose experiences and bafflement have us asking: Can any race hold power without imparting a postcolonial impress upon everything it touches? And if that impress is neither intentional nor malign—if it is the exercise of soft-power so soft that nerf seems rigid in comparison—then how readily can that race be hated or even fought against?

Nnedi Okorafor’s “The Winds of Harmattan” is a wonderfully uncompromising tale told by an equally wonderful and uncompromising author. Set in a world that is familiar and yet is not exactly ours, and in a time that refuses to be yoked to any known epoch, a reader can either experience this as a tale where fantasy and magic realism elide or as a metaphor for what happens when persons have innate qualities that ensure that they will indeed rise above “their station” in life. Just remember that verb: rise.

In “As Able the Air” by Zack Be, we are ushered into a bleak future of apparently endless war. Subterranean drone-piloting warriors are assisted by advanced, almost (?) sentient AIs as they carry out the reconceptualized missions of one of the most nerve-fraying of all military assignments: EOD. But disarming bombs may not be the most crucial danger, not when the line between artificial and organic intelligence begins to blur, and protagonist and reader alike must wonder: “how can you really be sure where simulations end and reality begins?”

“Molting Season” by Tim Boiteau is another Gothic Noir in the strangest post-apocalyptic setting you may encounter this (or any) year. To say more is to spoil it, but every page deepens the mystery of exactly what has befallen our world, and the strange decisions and paths that may alternatively lead to its final salvation, perpetuation, annihilation—or just indeterminacy. In which we just might find an allegory for the times toward which we ourselves seem to be moving.

And just when you thought you had the various thematic and emotional currents of this collection well-plotted, you encounter “Automated Everyman Migrant Theater” by Sonny Zae. You will laugh, you will nod at the wisecracks, and at sacred cows lovingly gored. It’s an ebullient and parodic revisiting of one of the oldest tales ever told: players who wish to strut their rusty hour upon the stage one more time. But in this case, the stand-in for the Bard is mechanical, and his desperate company of players springs fully realized from a setting that seems the product of a five-Autobot pileup between the worlds of Cars and Transformers. This penultimate story is joyous, playful, waggish, and should not be able to work—but does, thanks to the bravura performance of its author.

In “The Green Tower,” Katherine Kurtz favors us with another tale in the much-loved (and much acclaimed) Deryni cycle. The shapes and exigencies of that world once again echo those of our own, with characters that ring as true as any she has ever written and a story that both reminds us why this world is so cherished and that it is still growing. And, in so doing, “The Green Tower” demonstrates why its setting and author remain, truly, evergreen.

A Confession

And to conclude, a confession: I usually do not gravitate toward collections. My normal reflex is to reach for a novel, anticipating a deep, long, detailed dive into a world and its characters.

However, in case you should happen to share my predilection, my advice is to put that aside, at least long enough to get lost in this extremely well-crafted and often surprising Writers of the Future annual collection. Whatever preconceived notions you might possess when you first crack its cover, you will have entirely—and gladly—shed by the time you close it.

Dr. Charles E. Gannon‘s Caine Riordan hard sf novels have all been national best-sellers, and include four finalists for the Nebula, two for the Dragon Award, and a Compton Crook winner. The most recent, Marque of Caine (2019), was also a springboard for a side series, Murphy’s Lawless, that launched in 2020. His epic fantasy series, The Vortex of Worlds, debuts in 2021. He collaborates with Eric Flint in the NYT/WSJ bestselling Ring of Fire series, has written two solo novels in John Ringo’s Black Tide Rising world, and co-authored three volumes in the Starfire series. He’s also worked in the Honorverse, Man-Kzin, and War World universes. Other credits include lots of short fiction; game design/writing and years as a scriptwriter/producer in NYC.

As a Distinguished Professor of English, Gannon received five Fulbrights. His book Rumors of War & Infernal Machines won the 2006 ALA Choice Award for Outstanding Book. He is a frequent subject matter expert for national media venues (NPR, Discovery, etc.) and for various intelligence and defense agencies.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!