Dreaming Up Fabulous Places

Picture me: I’m nine years old, lying on my back beneath the skylight in my bedroom, rough carpet biting into my shoulders. I’m reading The Hobbit, enthralled. It’s summer. My mom is somewhere downstairs, yelling for me to get outside and play. I pretend I don’t hear her. I’m not there, you see. I’m in Mirkwood, starving with the dwarves and stumbling after elfish feasts in the dark. The last thing I want to do is go outside and play.

When I was a kid, I started making up imaginary places. Even before I read Tolkien, I was constructing cosmologies for my He-Man figures and establishing a chain of command among my stuffed animals. At the beach, the sand castles I built each had a story to them. They got names: Rampartiste, Gondria, Trudéal. I was the kid who wondered at the economic structure of Candy Land—did they eat it? Was the candy in the landscape distinct from the candy that made up their bodies? Did anybody ever get eaten and, if so, what was the punishment?

I was a weird kid. I know.

Fast-forward to 1991. A friend of mine is telling me about this game called Dungeons and Dragons. “Is it like a video game?” I asked, trying to wrap my head around it.

“No! You just write up your character on a sheet of paper and then somebody is the Dungeon Master.”

That piqued my interest. “What’s the Dungeon Master do?”

“He makes up the world and the monsters and stuff. Then you go and fight them.”

Makes up the world, you say? At that point, I had notebooks full of video games I wanted to create, primarily because those were the only things I knew how to script (level-boss-level-boss—a pretty simple plot). I tossed them away and started writing my own Dungeons and Dragons world. My parents gave me a copy of the 2nd Edition Advanced Dungeons and Dragons Player’s Handbook for my 13th birthday. That book changed my life.

Dungeons and Dragons carried me along my obsession with building worlds until I got old enough to realize I couldn’t make a living playing D&D (at least, I don’t think so. If anybody has any hot leads, let me know). So, how did a fellow make a living creating stories and worlds? After some trial and error (tried acting, directing, and a bunch of theater stuff), I settled on writing science fiction and fantasy. Mostly fantasy.

I have always thought of myself as more of a novelist. Novels were what I grew up reading, and novels were what I wanted to write. When I got out of college, I rejected the prospect of a stable career teaching high school English and, instead, flung myself into writing novels, figuring I could make a living at it after a few years.

Okay, you can stop laughing now. No, seriously. Cut it out.

Anyway, after getting my MFA in Creative Writing from Emerson College in Boston, I started to figure out that short fiction could give me the ability to hone my craft more effectively. It also could give me the opportunity to submit more work and possibly get some publishing credits that might help me towards my eventual goal of being a novelist. I put the novels on hold for a bit and threw myself into short fiction.

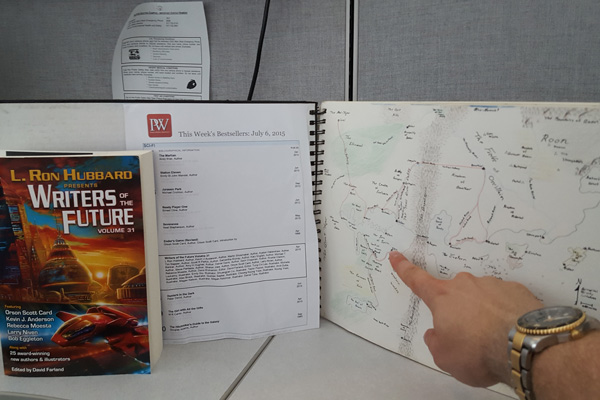

Auston holding up the Publishers Weekly Bestseller list for Writers of the Future Vol 31

“A Revolutionary’s Guide to Practical Conjuration” was probably my tenth entry into the Writers of the Future Contest (before my win, I got one Honorable Mention, two Semifinalists, and a Finalist finish). The story is set in a world I’ve been creating for years and is far, far bigger than just the city of Illin. The challenge for me was getting the giant, sweeping landscapes of my imagination to fit into a short story. Abe’s story is part of a larger tapestry, but the story also needs to stand on its own. That took some doing. When I sent it into the contest, I was on the verge of trunking it—I didn’t think it worked. Shows what I know.

Meanwhile, the week before I found out I won the Contest, I was offered a three-book deal through Harper Voyager. The last year has been a whirlwind of writing, deadlines, and learning the publishing industry in a very hands-on, no-holds-barred kind of way. The contest win has been a vital part of what success I have had thus far, and will continue to guide me in the future.

An omnibus of my first two books, called The Oldest Trick, releases on this August 11th (in e-book form). I am currently working on the fourth book in the series and, in the photo, you can see the wall of index cards in my office I used in the final stages of editing the third book. I’m off and rolling and I don’t intend to stop, and the Writers of the Future Contest has given me an edge in the business that is frankly irreplaceable. For that, I am eternally grateful.

Guest Writer post by Auston Habershaw

Writers of the Future Contest Winner

Author of “A Revolutionary’s Guide to Practical Conjuration”

available in Writers of the Future Volume 31

Additional articles and resources that may be of interest:

World-building in Science Fiction and Science Fantasy: A Look into Battlefield Earth and Dune

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!